``We have to go through the woods, to the house of an old lady who lives by the lake,” Mei Ling said, as I stowed her carefully in the bag so she wouldn’t fall out. ``we have to ask her the way to the camp of the Amazons.”

An old lady who lived in the woods? ``Will we be leaving a breadcrumb trail,” I said, only half joking.

``There will be no need – I know all the ways through the woods,” Mei Ling said.

So we set off on foot. It was a sunny day, but not too warm for my jacket. I felt quite festive and all I heard as we set off was the lonely barking of a dog from the gypsy camp.

On the way over the bridge I called into the mill for some bread for the journey and the baker wished me luck. He was a bonny young man, with a nut brown face and curly hair. I saw two pretty children playing outside as I left.

On the way, Mei Ling told me some hair raising things about Baba Yaga, the old woman who lived in the forest. I found her description of the fence around the cottage quite unnerving – apparently it was made of human bones.

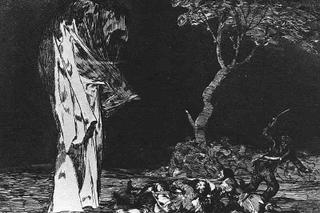

She sounded like an evil old witch, but it was clear that Mei Ling had a lot of respect for her, and she seemed unafraid. But then, she was a china doll. I got less optimistic when we reached the forest. As we walked along a narrow, twisting path overgrown with tree roots and hedged in by thick shrubs, it seemed to me we were going into an area where light could not penetrate.

When I judged the time to be about mid morning, we stopped and ate some of the bread. Mei Ling ate daintily, refusing the crusts. I had some water with me and we sipped from the bottle, but I realised I should have brought more food with me – I had thought there would be berries and other wild food, but the forest was too dense and dark to offer much in the way of berries. There were mushrooms – or some sort of fungi – but I thought it wise not to experiment.

In spite of Mei Ling’s assurance that she knew where we were going, I felt completely lost, as if we were going round in circlers. I was certain we were passing the same glowering oak tree several times.

But it seemed she did know, because all of a sudden the path forked. One fork led off into some unprepossessing undergrowth – the other had a rickety sign that said No Junk Male, although I couldn’t see a mail box anywhere. This was the path Mei Ling told me to choose.

Ahead of me was the fence Mei Ling had spoken of – the palings were jagged splinters of bone topped with grinning skulls. The gate hung lopsided on its hinges, swinging back and forth with a mournful squeaking noise.

Over the top of the gate I could see a house leaning at an odd angle and – moving.

``The house is falling over,” I said in alarm.

``No, it’s probably just having a scratch.”

I saw what she meant as I inched through the gate. The house was scratching – it stood on two scrawny chicken legs and it was scratching the earth like a chicken – two steps forward, scratch, scratch, then one step back to see what it had exposed. There were two windows either side of a porched door, and these looked for all the world like eyes and a beak. Even the walls and the roof were covered with russet red feathers.

Seeing me, the house stopped scratching and folded its chicken legs neatly. Now it looked like a proper little house, foursquare on the ground.

``Knock on the door,” Mei Ling urged.

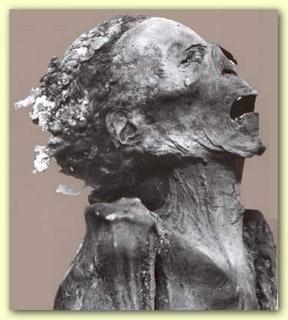

There was a knocker hanging there – a human skeleton hand curled into a fist. As I reached gingerly out to take hold of it, the skeletal fingers suddenly straightened out and shook my hand cordially. Then the door swung open and I found myself looking at the ugliest old woman I had ever seen.

She had warts on her face with hairs growing out of them. Her legs were the same as the house, scrawny and chickenlike, and she was dressed in an eclectic collection of skirts, aprons and a peasant blouse and vest that had certainly seen better days.

The first thing she said to me was, ``Do you come here of your own free will, or because someone sent you?”

I was about to protest my free will, and then I hesitated. Suddenly I wasn’t sure.

``Well – I said - ``actually, on the one hand I was told to come here – but on the other hand, I did choose to go – so I’m not really sure.”

She smiled at that, baring a formidable set of teeth that looked like iron.

``Good answer,” she said. ``Well, it looks as if I don’t get to eat you today. Pity,” she added, eyeing my ample hips. She stood aside and I went into her extraordinary home.

I found it strangely comforting. It looked like my Grandmother Bridget’s caravan, with bundles of herbs and onions hanging from the roof, and handcrafted items everywhere. There was a good smell coming from the pot on the stove, that made me twitch with hunger. Baba Yaga cleared a small rickety table – by tossing everything onto a spare chair – and indicated I should sit down. Soon I was tucking into a thick stew fragrant with herbs. To my relief, there was no meat in it, just turnips and barley and thick wedges of potato.

Mei Ling had a small amount as well, and a sip of water. She and Baba Yaga seemed to know each other well, and chatted happily through the meal. It was growing dark outside, and the warmth of the cottage, and the heavy meal, was making me feel sleepy.

``Our guest is tired,” Baba Yaga cackled. ``Well, you should sleep now, because we rise with the dawn here and I have some work for you to do.”

She gave me a rough cot by the fire, and I lay thankfully down, my bag on the floor beside me, and Mei Ling resting on the pillow. In no time at all, I was asleep.

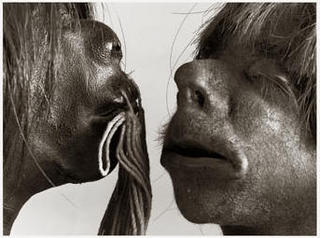

The sound of a horse’s hooves woke me, galloping up to the cottage. I jumped out of bed, pausing only to pick up Mei Ling, as Baba Yaga opened the front door and light flooded in. But what a changed Baba Yaga! Now she was a graceful young woman – only the flash of her iron teeth as she smiled at her visitor gave her away.

I peeked over her shoulder. I saw a knight on a white horse, his armor so bright that it cast rays of light.

``Good morning, my bright dawn,” Baba Yaga said playfully. ``What does the morning bring?”

``Fresh mushrooms, sorrel and wild thyme for your breakfast eggs,” the knight said, bowing low and offering her a basket filled with these goodies. ``And a daisy from the dew sprinkled fields.”

Baba Yaga took the daisy, and gave her white knight a flirtatious smile.

``Nothing else to report, my lady,” he said, ``the morning dawns fair and clear on your forest.” And with that he turned the horse and galloped away.

``Mushrooms for breakfast,” Baba Yaga cackled. She was a crone again, and she stood the basket on the table. ``That’s your first task,” she said to me. ``Collect the eggs.”

I followed her out of the cottage. She spoke some strange incantation at it, and at once it rose, with a great cackling and ruffling of feathers. Lying underneath it, between the chicken legs, were six freshly laid brown eggs.

``These eggs are not free,” Baba Yaga said. ``If you want them you must pay for them – the cottage, not me. Leave something of value, or the cottage will sit on you and squash you before you can escape.”

What would a cottage that looked like a chicken (or a chicken that looked like a cottage) consider to be just exchange for its eggs? I looked helplessly at Mei Ling.

``You must give up one of your songs,” she whispered. ``A favourite, one you value – sing to it when you take the eggs.”

So I started singing as I walked between the legs of the chicken house. I was singing as I bent to pick up the eggs one by one, and singing as I turned to walk back to Baba Yaga. The legs remained upright, so I continued to sing as I walked safely out from under the house.

And do you know, I cannot for the life of me remember what song it was I sang to the chicken house. It has gone forever, and all I know is that it was precious to me.

Another incantation from Baba Yaga, and the house once again sat down. She cooked a fine breakfast of scrambled eggs with sorrel and wild thyme, and mushrooms on the side.

After breakfast, Baba Yaga wanted to go herb gathering in the woods, so Mei Ling and I followed her through the twisting paths. She stopped frequently to pick some plant or another and told me what each one was for – I realised I was in the presence of great natural wisdom and tried to make notes so I wouldn’t forget. I made little sketches of some of the herbs as well.

On the way back to the cottage we met another knight, this time in red armour and riding a chestnut horse. I looked back at Baba Yaga and was not surprised to see she had changed again. Now she was a mature woman in the full bloom of her beauty, but with lines of experience and wisdom just beginning to be etched around her eyes and mouth.

``Hail, my Red Sun,” she said. ``What does the day bring?”

``Tomatoes ripe from the vine,” the knight said, bowing low to both of us. ``And full blown roses to reflect your beauty.”

``Salad for lunch,” Baba Yaga said happily as the knight rode away. Her gnarled fingers touched the bloom of the roses gently.

After a very good lunch of salad greens and tomatoes tossed with herbs, she handed me a scroll of parchment.

``Your second task is written here,” she said. But when I unfurled it, the parchment was blank.

My face must have looked much the same, because Mei Ling rolled her expressive eyes and sighed gently. Obviously, the answer was very simple and I should know it already.

``My glasses!” I said, and I grabbed the purple specs from my bag. With these on, I could clearly see Baba Yaga’s spidery writing.

``Name that,” it said, ``which you fear most, so much that it blinds you to what you already have. Cast this parchment into the fire and be rid of it forever.”

I thought for a while, and wondered what I would be like without that fear – would I really be myself any more? But then I took up the quill, and I wrote – but I can’t remember what I wrote, because as soon as the parchment burned up in the flames, I was free of it, and I saw that there was so much else in my life that was more important and I knew I could pursue my creative dreams unhindered by it.

So in one morning I had given up something very precious to me for a few eggs, and something I no longer needed. Mei Ling and Baba Yaga were nodding at each other in a conspiratorial manner and I wonder what else they had in store for me.

As the afternoon wore on, I helped Baba Yaga prepare some of her potions and wrote the recipes down for future reference. She used the petals of the rose to make an exquisite lotion which she gave to me in a small bottle.

We settled by the fire and I wondered what my third task would be. I had a feeling it would be the last, and that I would be leaving Baba Yaga very soon. I was sad about that – I found her company delightful, and I had lost my fear of the old fairy tales. Baba Yaga had so far proved to be a vegetarian, anyway.

Suddenly we heard the thunder of hooves approaching the cottage. Baba Yaga opened the door, but this time she did not change. Looking over her shoulder, I saw a black knight on a black horse, studded with stars. There was a silver crescent moon on his helmet, which he raised. I saw the kindly and wise face of an old man.

``Good Eve, my Dark Midnight,” Baba Yaga said. ``What does the night bring?”

``News of travellers heading to the Camp of the Amazon Queen, and your guest must join them,” he said. ``And a star from the sky for my dear love.” He handed her a diamond so bright it flashed with a million rainbow sparkles.

After the black horse and rider vanished into the darkness, Baba Yaga turned to me.

``One more task,” she said, ``then you must be on your way.” She looked at me with her wise old eyes. ``I am the guardian of the waters of life and death,” she said. ``I can command the Sun, the Moon and the Stars in their courses. I can change time.” She delved into her capacious pocket and drew out three objects hanging from leather thongs, which she laid on the table. One was a small daisy with a heart of gold, and next to it was a finely wrought rose in full bloom. Lastly there was a lump of coal, twisted in a loop of silver wire.

``Choose carefully,” she said.

I understood, as I looked at the pendants, what each one represented. The daisy was the morning of my life – the young woman, setting out with freshness and hope. The rose was the afternoon of my life – the mother caring for her children and nurturing their dreams. But the lump of coal – surely that could not represent the years ahead?

My hand reached out for the rose, because the happiest years I had known were those when my children were young. But they were grown now, and I had grandchildren. If I changed my time, I would be changing theirs as well.

I reached out for the daisy, and again I hesitated. It would be wonderful to be young again, but why would I go that far back when I had finally learned not to long for the past, or fear the future?

So my hand closed around the lump of coal – and as I lifted it up to hang around my neck, it changed into a diamond.

The Grotto della Sibilla in the Umbrian Mountains which was first mentioned in classical legend. Guerino the Wretch reaches a mountain pass near Norcia in Umbria where he meets with the Devil. The Devil, of course, wants Guerino's soul and tempts him by describing a subterranean kingdom where every delight will be his. Seemingly, in this kingdom, trees flower and fruit at the same time and there is no pain or age or sorrow.

The Grotto della Sibilla in the Umbrian Mountains which was first mentioned in classical legend. Guerino the Wretch reaches a mountain pass near Norcia in Umbria where he meets with the Devil. The Devil, of course, wants Guerino's soul and tempts him by describing a subterranean kingdom where every delight will be his. Seemingly, in this kingdom, trees flower and fruit at the same time and there is no pain or age or sorrow.